St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, Durango, CO

Sixth Sunday After Pentecost

June 26, 2016

In today’s gospel 1 Jesus is traveling from his home region, Galilee, through Samaria to Jerusalem in Judea. Now, Samaria was an interesting place. It separated two Jewish populations, Galilean Jews and Judean Jews, from each other geographically. The residents of Samaria were related to the Jews; they shared a common ancestry and stories from the Hebrew Scriptures. But Jews and Samaritans were alienated from each other because of their religious and geopolitical past. Jews did not consider Samaritans true followers of Yahweh because their ancestors, though originally Israelites, hadn’t endured captivity and exile with the Judean elite who were taken to Babylon around 586 BCE 2. When the Judeans returned from exile around 540 BCE to rebuild Jerusalem and the temple, they refused to let the descendants of Israel who had remained in the area of Jerusalem participate in the project – and as a result those people and most other Yahweh worshipers moved the focus of their worship to Mount Gerizim in Samaria. Jews in Jesus’ time considered the Samaritans apostates and idolaters. Jews believed that Samaritans understood God incorrectly and that they worshipped him in the wrong way at the wrong place. And the Samaritans felt likewise.

It should not have been surprising, then, that Jesus was rejected when his advance delegation of disciples tried to set things up for his arrival in a Samaritan town. Those Samaritans probably believed that because Jesus’ “face was set toward Jerusalem” Jesus was not authentic prophet: he clearly didn’t understand God rightly and was going to worship him in the wrong way at the wrong place. But Jesus’ disciples, in Luke’s gospel, had just seen Jesus heal the sick, raise the dead, feed the thousands, calm storms, cast out demons, and be identified by God as God’s son during a mountain top transfiguration. By now, most of the disciples believed Jesus to be the Messiah – and probably a re-incarnation of Elijah (remember Elijah and Moses are the two guys who show up and stand with Jesus during the transfiguration), Elijah, perhaps ancient Israel’s most powerful prophet. Some of those disciples were undoubtedly familiar with a particular story about Elijah in the Hebrew Scriptures 3. In that story, Elijah was dealing with a king of Israel (Ahaziah, the wicked son of Ahab and Jezebel) who worshipped Baal-zebub instead of Yahweh and did so in the wrong way at the wrong places. When that King sent soldiers to fetch him, Elijah demonstrated his prophetic authenticity by calling down fire from heaven on two separate groups of them (one commander and fifty men each). And the fire “consumed” them. So, Jesus’ disciples probably figured why not ask the Messiah and new Elijah-like prophet of God whether or not he’d like to demonstrate his power by doing the same to those uppity Samaritans who didn’t understand God rightly and worshipped him in the wrong way at the wrong place.

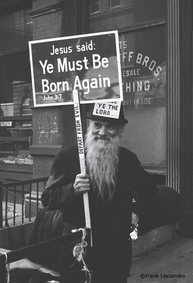

But Jesus, here, refuses to follow Elijah’s example and use his methods. Jesus makes it clear to his disciples that following him does not entail calling forth violent retributive exhibitions of his power. Instead, he rebukes his disciples for their self-righteous suggestion (which they may well have derived from the Elijah story just mentioned) and simply moves on to the next town. But, as he continues traveling, Jesus begins to teach the disciples through a series of three hyperbolic proverbs what following him actually will entail. It will entail the possibility of discomfort and insecurity: Jesus, unlike foxes and birds, will have nowhere to lay his head – and so may his disciples. Following Jesus will also entail being fit for and proclaiming the Kingdom of God and, therefore, should not be delayed by excuses – even excuses that are ordinarily valid.

And why is Jesus so concerned that his disciples not engage in excuses and delays when being asked to follow him or while actually trying to do so? What’s the rush? Growing up, I was taught that deciding to follow Jesus was one of the essential steps in “getting saved.” Any delay, therefore, risked one’s eternal destiny. But I think there may be more to Jesus’ teaching about following him urgently than saving our own souls. I think that “following Jesus” means not just deciding to become his disciple; I think it also means urgently living into what Jesus called the Kingdom of God, into his vision of human and divine society, into human interactions wherein we consistently love God and love our neighbors as ourselves. Though God is sovereign, Jesus seems to be saying that delays and excuses on the part of those professing to follow him will have consequences; they may constrain the activity of God’s love expressed through us into the lives of others.

One fall night in the late 1980s, I was on call at the hospital to admit patients who didn’t have their own physician. At about 2:00 a.m. I was contacted by the Emergency Department and asked to admit a young man with intractable vomiting and diarrhea – probably viral gastroenteritis. Though gastroenteritis can frequently be managed as an outpatient, such management was impossible in this case because this young man had no money, no home and was hitchhiking through the area. My response was somewhat less than enthusiastic, but I did come to the hospital, examine the patient, and admit him. He was pleasant enough, but he was dirty, his clothes were worn and grimy, and he was very dehydrated. I ordered the appropriate treatments and went back home to bed. Within twenty-four hours he was much improved; his diarrhea had stopped, and he was tolerating oral liquids. On the morning of the second hospital day, the hospital case manager told me the young man should be discharged, and I agreed even though he still looked a bit miserable. I discharged him, made rounds on my other hospitalized patients, then got in my car and drove toward my office on the north end of town. But as I neared the office, I saw my discharged patient, sitting hunched against his worn back-pack, and shivering on the side of the road in his ragged clothes, trying thumb a ride with snowflakes swirling around his face and beard. I don’t often hear Jesus’ voice telling me specifically how to follow him – and to do so quickly, but that morning I’m pretty sure I did. And, as you might guess, I began mentally reciting excuses for not doing so. I didn’t need to bury a parent or say goodbye to my family, but there was no homeless shelter in Durango back then, and the soup kitchen wasn’t open. I had already given him several hundred dollars worth of free professional medical care at the hospital. Someone else might pick him up. Lots of patients were waiting for me at the office – and some of them might be sick. They needed me; I was their doctor.

Fortunately, for the young man, I finally followed Jesus (without much delay) – albeit imperfectly. I drove him to a local motel and paid for two nights lodging. I now wish I’d made more arrangements for food and possibly transportation. The point I want to make, however, was the importance in this instance of following Jesus urgently – not in terms of accepting a belief system so that I could be saved – but in terms of not missing an opportunity to act in love toward another human being and meeting his urgent physical need in real time. Following Jesus means that we do things as he would do them – and that means we do at least some of them now. Without excuses. Without delay.

Currently, many of us are very concerned about the increasing violence in our country and the world. Since most of the justification on every side for such violence seems to be framed in terms of resisting evil and establishing justice, many Christians and other persons of good will are trying to develop effective ways of responding to evil and injustice that are nonviolent. André Trocmé, leader of a French village that nonviolently resisted the Nazi’s and sheltered Jews during the Second World War, insisted that nonviolent responses to injustice, to be effective, must be initiated “in time.” He told a story about being a twenty-year-old soldier in the French army in 1921 and being sent out with other French soldiers to map a dangerous area of Morocco. Because of the danger he was issued a gun and ammunition. But, during the mission, his lieutenant discovered that Trocmé was unarmed. When confronted, Trocmé explained that he was a Christian and could not kill; therefore, it made no sense for him to carry weapons. The lieutenant took Trocmé to his tent, offered him a cigar, and had a conversation with him about timing. He led Trocmé to understand that:

- they were now only twenty-five isolated men in an area where attack by brigands and dissidents was very likely;

- if other soldiers had done this, they might be massacred; and

- Trocmé’s refusal to bear arms was too late – he should have made his choice and acted sooner.

Later, as the pastor of the small French Village, Le Chambon, Trocmé and other Christians, did follow Jesus “in time.” Along with other Chambonai, they began, after the German conquest of France, by continuing to run a local school teaching principles of international nonviolence and by refusing to stand around the school flagpole every morning as commanded by the French authorities to give fascist salutes to the new flag of Vichy France. Next, they refused to ring the church bells to celebrate the formation of a new French police unit modeled on the Gestapo. Then, they refused to identify the Jews in their community when French police sent busses into Le Chambon to round them up. Later, when Jews from all over Western and Eastern Europe began showing up in their town, the Chambonai sheltered these strangers in their homes, despite the risk to their own lives, the risk to their children’s lives and their meager winter food supply. By the time the war ended, Trocmé and the Chambonai had also learned how to forge false ID cards for Jews and help them escape to safe countries via underground railroads. When the war did end, the Chambonai sheltered and protected captured German soldiers, who elsewhere in France were often being rounded up and summarily executed. They followed Jesus consistently – and for the most part – without excuses and without delays.

And finally, all this leads me to ask the question: What might our community, and perhaps even our world, look like, if we as Christians helped one another follow Jesus by resisting evil and establishing justice and doing so nonviolently but urgently, without excuses and without delays – “in time” as André Trocmé would say? May God grant us the opportunity to find out.

___________

1 Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version, Luke 9:51-62

2 Diarmaid MacCulloch; Christianity: the First Three Thousand Years, p. 62

3 Holy Bible, New Revised Standard Version, 2 Kings 1

4 Philip P. Hallie; Lest Innocent Blood be Shed, p. 93

RSS Feed

RSS Feed